The Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) population is growing at a swift pace in the United States. Despite the increase — four times the rate of the nation overall — these groups who hail from the thousands of Polynesian, Micronesian, and Melanesian islands that dot the Pacific Ocean remain overlooked and understudied. Especially from a mental health perspective.

While those struggles aren’t necessarily so different from the U.S. collectively, some ocean-size barriers remain.

One gigantic hurdle is that NHPIs tend to avoid mental health treatment. It’s not entirely understood why, but stigma appears to be a driving force, as does a history of marginalization.

Stigma frequently has been cited as a major hurdle to mental health treatment and recovery. NHPIs often view mental illness as a moral failing — a person afflicted should be able to will themselves better and forgo medical treatment. Or wait it out, believing it’ll resolve on its own in due time.

Such stigma may also fuel a tendency to distance oneself from someone with depression or some other disorder. Sometimes the person is not just viewed as ill, but dangerous.

When people are stigmatized, they might suffer poor self-esteem, which is also harmful to mental health.

In terms of marginalization, decades (or longer) of historical trauma have resulted in a number of disparities. Socioeconomic opportunities are slim.

Health coverage — if there is any — doesn’t cover very much, even though members of this population face higher rates of disease, including obesity, diabetes, and cancer. All can raise the likelihood of mental illness.

Those factors combined with lingering stigma means getting help for any number of disorders, including substance use, may prove more challenging for members of the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander population — yet all the more essential.

Recognized as Unique

Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders were long lumped together with Asian Americans when it came to collecting data. In many cases they still are.

In 2000 the U.S. Census made Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPI) a category distinct from Asian Americans. That’s fitting, perhaps, since the Asian American population is extremely diverse.

It’s also a growing demographic, with Asian Americans the fastest-growing minority in the U.S. with a population of 22.2 million in 2017, or about 6% of the U.S. population. NHPIs make up a much smaller group — 1.6 million.

Of that 1.6 million:

- 614,572 are Native Hawaiians

- 202,268 are Samoans

- 156,482 are Guamanians or Chamorros (native people who lived in Guam, the Mariana Islands, or other islands)

NHPI groups tend to be broken down into Polynesian (including Native Hawaiian and Samoan), Micronesian (including Guamanian or Chamorro), and Melanesian (including Fijian and Papua New Guinean).

The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander heritage population within the U.S. is expected to nearly double, to 2.9 million by 2060. (They still — even in combination with other groups — are projected to amount to less than 1% of the U.S. population for the next few decades.)

Diversity

Despite a shared history of racism, discrimination, and exclusion — some of which continues to this day (“China virus” or “China flu,” anyone?) the Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander (AANHPI) population is extremely diverse, from more than 50 countries, representing a number of languages, cultures, customs traditions, colonial histories, and more than 20 major religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Catholicism, Taosim, and polytheism.

AANHPI groups are also diverse in appearance, with varying traits that include eye shape, skin tones, hair texture, and more.

Stereotypes

Asian Americans are no strangers to being stereotyped. The model minority myth — that they tend to be highly educated and well-paid, and hail from two-parent families and a community that watches out for one another — persists. On one hand, it sounds like a compliment (wealthy, well-educated), but it’s just another way to divide.

Using the model minority myth is also another way to overlook disparities. Asian Americans experience poverty, mental illness, and other societal ills too — some groups more than others. (Plus, racist thinking puts the focus on differences instead of what we hold in common.)

Overall, Asian Americans have low rates of drug and alcohol use disorders, but that generalization might hurt those who need help. Pacific Islander or mixed heritage populations tend to be more vulnerable.

Racism and Mental Health

Despite racism being a very real problem, it’s not always addressed, particularly in mental health. Training focused on racial trauma remains more of an exception rather than the rule.

That’s troubling on many levels, since racism not only affects the individual who experiences it firsthand, but there are intergenerational and far-reaching wounds, from stories passed on from old to young, or from vicarious experiences via social media.

Racism can negatively affect a person’s health in many ways, including:

- Interfering with sleep

- Prompting people to eat too much (especially sugary or carbohydrate-heavy comfort foods) or too little

- Elevating stress hormones, which when they stay escalated, can lead to weight gain, reduced healing, and eventual heart disease

- Worsening symptoms of anxiety and depression (which in turn can be made worse by a poor diet)

Some research even has found that trauma may affect the individual on an epigenetic level (when environment or behavior can alter how genes work), where parents pass changes to their offspring. A child of a parent who experiences racism, for example, may be more sensitive to experiencing or even hearing about discrimination.

NHPI populations are no strangers to racism, either. More than half the Native Hawaiian population was wiped out by disease in the 1800s, courtesy of Western colonizers. Many customs, and a lot of the culture and language were scrubbed.

Also located in the Pacific, the Marshall Islands was where the U.S. conducted nuclear tests for more than a decade after World War II. The inhabitants and the land were subject to fallout as a result.

NHPI Problems

In terms of mental health issues, a one-size-fits-all approach rarely works.

While Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders represent a small fraction of the Asian American population, they still face their own set of struggles, including more socio economic troubles and more cases of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes compared to other Asian Americans.

As for mental and behavioral health findings, the information on NHPI populations are somewhat lacking.

For 2018, studies found NHPI had rates of mental illness that were similar to those experienced by non-Hispanic whites — if data for a specific category was even available.

One thing was certain, however: NHPI are far less likely to receive mental health treatment, either via prescription medications or mental health services.

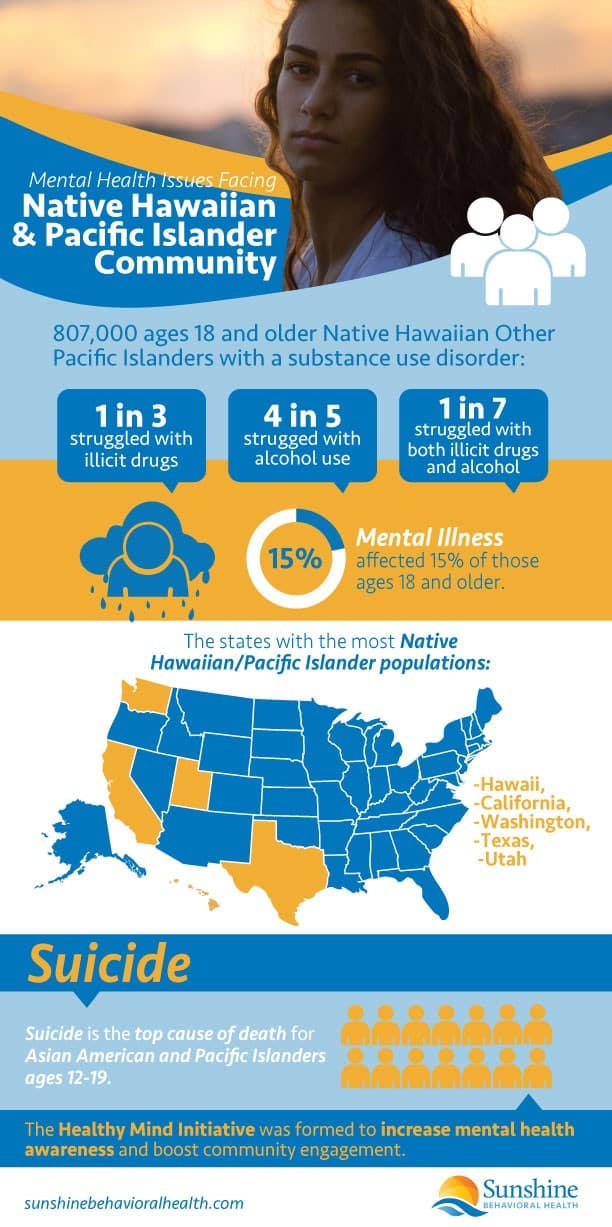

A lot of data still puts Asian groups with Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (ANHOPI) populations, so pitting them against the overall U.S. population makes them appear less prone to suicide, mental illness, or substance use, but it overlooks many subtleties within the subgroups

Hawaii has a population of about 1.4 million, and 3.2% of adults have a serious mental health condition such as major depression or bipolar disorder. Only a third of those individuals get treatment. That’s the overall population, though, and Hawaii is very diverse.

According to the U.S. Census, Asians alone are 37.6% of Hawaii’s population, while 10.1% are Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander: Meanwhile, 10.7% are Hispanic or Latino; two or more races account for 24.2%; white alone make up 25.5%; and white alone/non-Hispanic or Latino, 21.7%. Blacks and American Indian/Alaskan Natives make up the remaining 2.2% and 0.4%, respectively.

Asian Americans overall are far less likely to seek mental health treatment. That could be a cultural choice (to seek help is to show weakness or insult the family, perhaps) or it could be an economic decision (lack of money or insurance coverage).

A 2019 paper published in Psychiatric Services looked at 223 adults of Samoan or Marshallese heritage. (Marshallese people are from the Marshall Islands.) A significant number of respondents admitted to depression, anxiety, and alcohol use, including:

- Major depression, 21%

- Generalized anxiety disorder, 12%

- Alcohol use disorder, 22%

Many respondents admitted they needed or wanted mental health service, but few sought help. National admissions data has shown NHPIs and Asian Americans pursue treatment for substance use disorders at half the rate of other groups.

And even though Asian Americans and NHPIs make up about 6% of the population, they make up only about 1% of admissions. In areas where there is a much larger Asian American and NHPI population (California, for example), the rates are even lower.

In terms of suicide alone, both for ANHOPI and overall U.S. populations, the rate is higher among males, and it’s higher for younger people, and for men older than 75.

Despite few studies focusing on NHPI communities and their mental health, there is some information:

Mental health

- Native Hawaiians report more depression over whites, but with no real difference between Native Hawaiian men and women with depressive symptoms.

- Schizophrenia tends to be lower among Native Hawaiians than whites (in Hawaii), but Native Hawaiian groups tend to be hospitalized more than Asian Americans overall.

- Men in Hawaii die by suicide at a 3 to 1 ratio over females. In Guam, 90% of suicides are male.

- In Western Samoa, the suicide rate for every 100,000 people was 64 deaths for males and 70 for females. In Guam the rate was nearly five times higher for men ages 15-24, with 49 males taking their lives, compared to 10 for females.

- In Micronesia 11 times more young men die by suicide compared to young women (91 versus 8); and in Chuuk State, Federated States of Micronesia, young men also died at a rate 15 times higher than females (182 versus 12).

- NHPI adolescents have higher rates of depression (36.1%) out of all U.S. racial groups, and overall, nearly twice the rate of attempted suicide (15% vs. 8%).

- More than 70% report delaying or avoiding mental health treatment, compared to 60% of the U.S. overall.

Substance use

In California, Pacific Islander males ages 11-18, compared to other racial and ethnic groups overall:

- Had higher lifetime and past-month smoking rates (18.7% and 39.3%), as well as lifetime and past-month methamphetamine use (12.8% and 11.7%).

- Shared the highest rates of marijuana use (22%) with African Americans, and the highest binge alcohol use rate (22.3%).

Methamphetamine (meth) use among Pacific Islanders (not confined only to California) is high; one study found that approximately 10 percent of Pacific Islanders had a dependence on methamphetamines. That’s in comparison to the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which found that 0.4% of the U.S. population ages 12 and older had a methamphetamine use disorder.

Education

NHPI also have the highest high school dropout rates among all Asian American groups — 7.6% — followed by Cambodians and Hmong (6.7%). The rates are higher than those of whites (5%) but lower than Black (12%) and Latino (27%).

While 27% of all Americans over 25 have a college diploma, and 44% of Asian Americans have a college degree, only 16% of Guamanians or Chamorros, 16% of Native Hawaiians, and 10% of Samoans have college degrees.

Samoan, Native Hawaiian, and Filipino youth, especially males, have said that teachers frequently stereotyped them as gang members or lazy.

Barriers to Help

There are a number of barriers to help. Sometimes, they’re common ones, such as budget concerns. But other issues also might prevent Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians from receiving treatment or therapy.

There are a number of barriers to help. Sometimes, they’re common ones, such as budget concerns. But other issues also might prevent Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians from receiving treatment or therapy.

Some of the obstacles to seeking help include:

- Being the minority in a group: Some people go to therapy and find themselves the only person of color there. Or they may be the only person who is the child of immigrants. Either situation can make them feel like they’re not truly understood.

- Fear of being labeled as “crazy”: There is an underlying fear that seeking mental health treatment is akin to admitting insanity.

- Shame: Seeking outside help implies the family is to blame for one’s problems.

- Community bonds: Interdependence is valued within the culture, so paying to tell a stranger about one’s problems rather than seeking help from one’s community is frowned upon.

- Cultures less receptive to therapy: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, compared to other races and ethnic groups, are often more reluctant to seek therapy. That could be due to any number of factors: faith, cultural values, language barriers.

- Stereotypes about achievement and finances: Most Asians (including Pacific Islanders and Hawaiians) are thought to be more economically stable. That in part is fueled by the model minority myth that all Asians are wealthy and highly educated. (NHPI tend to have a lower median household income in comparison to other groups.)

- Family pressure: Some feel overwhelmed due to high family expectations.

- Thoughts about strength and sacrifice: For some whose families came over as refugees and faced numerous hardships, the younger generations may not want to seem ungrateful to family sacrifices. They think older generations have suffered much more so theirs is weak in comparison.

- Beliefs about feelings: Silence is seen as a form of strength, so revealing emotions is a sign of weakness or a burden.

- Communication in the family: Some don’t know how to bring up mental health around their family members.

- Generational perspectives: Some members of older generations do not believe in mental illness.

- Differing expressions of feelings: Some may express negative emotions as physical pain.

- Previous experiences: Some will say, “I tried therapy and it didn’t help.”

There’s no one easy solution, but one study found that improving health care access and building better outcomes can occur by:

- Training and hiring more NHOPI medical professionals, including increasing the number of physicians.

- Offering more health care to areas that are underserved.

- Making it easier and more affordable to obtain medical care.

- Adding more cultural sensitivity to medical training (or, culturally competent care).

Culturally Competent Care

One size does not fit all when it comes to treating mental or substance use disorders.

Cultural competence, particularly concerning health, is important because disparities continue among various cultural groups in comparison with the U.S. as a whole.

Understanding culture is understanding a group’s beliefs, values, customs, and communication approaches. Culture can affect how a person feels about and responds to mental health conditions, health professionals, and treatments.

A culturally competent health care provider has knowledge of different cultural groups — an awareness of different customs, beliefs, values, practices, and attitudes, which they in turn use to better shape a treatment plan by working with the complexities of the groups involved and not forcing the dominant (usually white) culture on clients.

By better understanding diversity — or working to understand it — health care providers can adapt to or compromise with the community served, and are better able to work across cultures. The result tends to be better outcomes.

How to Find Culturally Competent Care

To find a culturally competent provider, the National Alliance on Mental Illness offers suggestions:

- Reach out to agencies or providers from your cultural background, or look for agencies versed in working with your culture.

- Ask friends and family for recommendations.

- Look online, or seek referrals from organizations in your area.

- If you have insurance, contact the provider for suggestions.

Don’t be afraid to interview potential providers to make sure they’ll be a better fit, either. It’s your time and (often) your money, too. Quiz them on the following:

- Are they aware of your culture’s attitudes toward mental health? If they aren’t, are they willing to learn?

- Are they trained in cultural competence?

- Are they bilingual, or any of their staff bilingual?

- How would they consider cultural identity in crafting a care plan?

- Does their office show signs of inclusion?

As you seek a provider or treatment plan, don’t be afraid to tell which values are vital to you. Tell them if you’d like your family involved. Take time and research your health issue — whether it be mental illness or a substance use disorder. The more you know, the better.

Other sources of information which help promote mental health awareness and offer resources include:

- Behavioral Health Equity. For Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander groups. The Substance Use Disorder and Mental Health Services Administration offers this resource, full of survey findings, agency and federal initiatives, and behavioral health resources. (The resources include options in different languages.)

- Healthy Mind Initiative. Offered by the Asian Pacific American Officers Committee to combat the high suicide death rate among Asian American and Pacific Islander youth.

- NNEDshare. A place to share and learn about resources with the goal of improving behavioral health care among diverse groups.

Mental Health Resources for the Asian American Community

Mental health resources

National Asian American Pacific Islander Mental Health Association – Lists behavioral and mental health services in different U.S. states

Special Services for Groups, Inc. (SSG) – Provides behavioral health services, recovery support, and prevention strategies for immigrants and people with limited English skills

Each Mind Matters – Discusses community mental health resources in English and other languages as well as information about private services

California Asian Pacific Islander Legislative Caucus – Contains community resources, including counseling and assistance for treating drug abuse

National Asian Pacific American Families Against Substance Use Disorder

Resources that address suicide

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline – 1a800a273aTALK (1a800a273a8255). You can also chat with someone by clicking this link.

Suicide Prevention Resource Center

Antidiscrimination resources

Stop AAPI Hate – Site that allows people to report incidents against members of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities in several languages

Resources for understanding Asian American cultures

Supporting Students from Diverse Racial and Ethnic Backgrounds – Explains how different cultures view mental health and includes resources for understanding cultures and finding assistance

WISE: Working to Improve Schools and Education – Information about different Asian American cultures, including resources for teachers who have students from different communities

Sources

Medical disclaimer:

Sunshine Behavioral Health strives to help people who are facing substance abuse, addiction, mental health disorders, or a combination of these conditions. It does this by providing compassionate care and evidence-based content that addresses health, treatment, and recovery.

Licensed medical professionals review material we publish on our site. The material is not a substitute for qualified medical diagnoses, treatment, or advice. It should not be used to replace the suggestions of your personal physician or other health care professionals.