The United States population is aging. In 2020, the average age in the U.S. is 38.2. In 2010, it was 37.2. That may not sound like a significant increase, but the rate is likely to accelerate. By 2034, the U.S. Census projects there will be more people 65 and older than 18 and younger.

The biggest reasons are that the post-World War II baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) have started to reach age 65 while the birth rate in 2020 is less than half what it was in 1950.

Among the many problems that this poses for society is caring for an aging population with substance use disorders (SUDs), particularly of prescription medications such as opioids.

The Opioid Crisis

Since the introduction of potent and purportedly addiction-free prescription opioids in the 1990s, SUDs have been on the rise among the general population. The White House declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency in 2017, but that just recognized a grim reality.

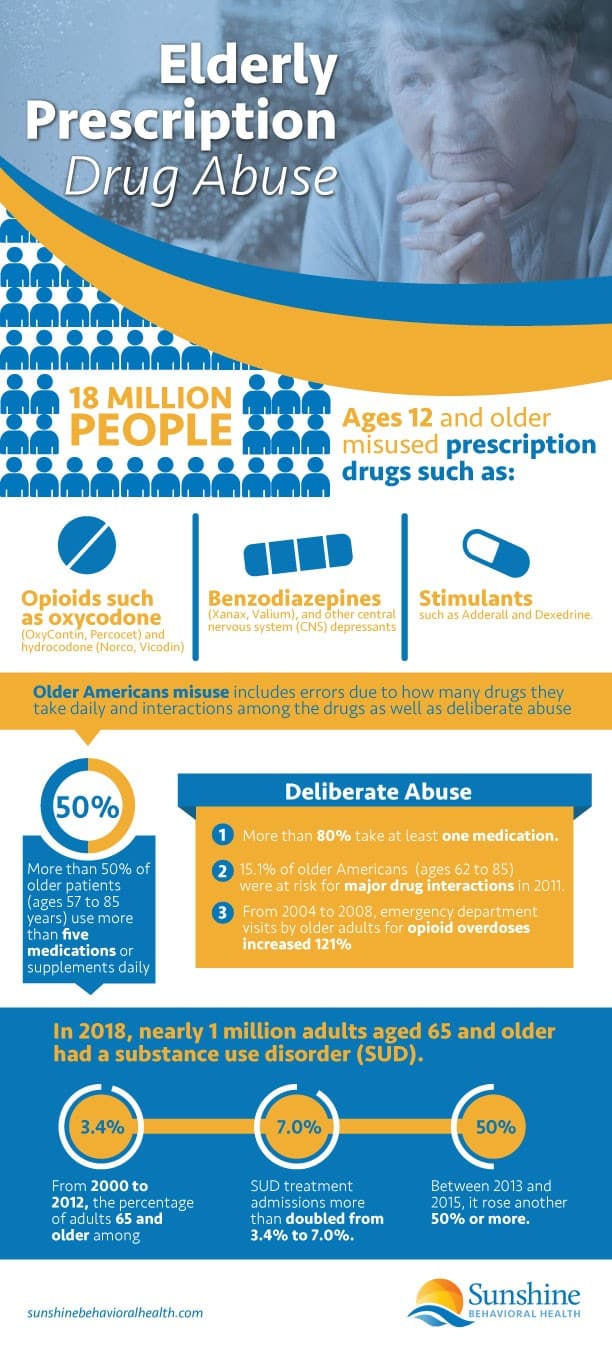

The 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) estimated that 18 million people — more than 6% of people aged 12 years and older — misused prescription drugs, including:

- Opioids such as oxycodone (OxyContin, Percocet) and hydrocodone (Norco, Vicodin)

- Benzodiazepines (Xanax, Valium), and other central nervous system (CNS) depressants

- Stimulants such as Adderall and Dexedrine.

Many of these are considered psychoactive or psychotropic drugs — any substance that changes the way you feel, think or behave — a broad term that also includes caffeine, alcohol, marijuana, and LSD.

Misuse is using prescribed drugs other than as prescribed (usually more often or in larger doses), using prescription drugs without a prescription, using illicit drugs, or using them in combination with other drugs or substances, including alcohol.

Elderly Prescription Drug Misuse on the Rise

Although substance use disorder is most prevalent among the young, it is also on the rise for older adults, those who were once considered elderly or senior citizens. Misuse by the elderly population is also apparently on the rise, but there seem to be more projections than hard statistics.

Part of the problem may be how you define who is elderly. Usually, for government purposes, older adults are considered to be 65 and older, in other uses, it can be as young as 50. This confusion makes it difficult to correlate statistics from different sources. So:

- A 2012 issue of Older Americans Behavioral Health, published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), projected the rate of elderly drug misuse would be 2.4% or 2.7 million by 2020 (up from 1.2% or 911,000 in 2001).

- The Administration on Aging and the Substance Use Disorder and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) projected the rate of elderly drug misuse would be 2.4% or 2.7 million by 2020 (up from 1.2% or 911,000 in 2001).

- A 2017 issue of The CBHSQ Report estimated a higher illicit drug use rate among seniors: 3.1% or 5.7 million in 2020 (up from 2.2% and 2.8 million in 2001-2002).

- SAMHSA also referenced other unnamed reports that put the rate at anywhere between 1% and 26%, depending on the kind of SUD : misuse, abuse, dependence, or addiction.

There are several reasons for this increase:

- More addictive medications, especially prescription opioids, became available over the last 20 years, incorrectly promoted to physicians as having a low risk of addiction.

- Aging baby boomers grew up more accustomed to using drugs, both legal and illegal, as well as over-the-counter (OTC) drugs and largely unregulated herbal or dietary supplements.

- Physicians routinely prescribe multiple medications to older adults, many potentially addictive.

What Drugs Are the Most Prescribed for the Elderly?

One-quarter of the elderly use prescription psychoactive drugs, including anxiolytics (for anxiety) and antipsychotics (for other mental health issues).

Among the other drugs most prescribed for older adults are:

- Antidepressants, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and other antidepressants

- High cholesterol reducers (antihyperlipidemic agents)

- Stomach acid reducers (proton-pump inhibitors or PPI)

- Muscle relaxants.

Complicating these figures is that many also take over-the-counter (OTC) meds and largely unregulated dietary or herbal supplements.

While these drugs do not always pose as much danger as opioids, benzodiazepines, and stimulants in themselves, they can have interactions that nullify, intensify, or otherwise alter how a drug affects you or cause harmful side effects.

Drug Interactions

Such elderly misuse isn’t necessarily — or usually — deliberate. More than 50% of older patients (ages 57 to 85 years) use more than five medications or supplements daily, sometimes called polypharmacy; about 80% take at least one.

Such elderly misuse isn’t necessarily — or usually — deliberate. More than 50% of older patients (ages 57 to 85 years) use more than five medications or supplements daily, sometimes called polypharmacy; about 80% take at least one.

Using so many medications can easily lead to accidentally taking more or less than prescribed.

Interactions may occur if older adults neglect to inform their physicians about the other drugs and supplements they are taking. These interactions may increase, decrease, nullify, or otherwise change the effects of medication.

One longitudinal study found that 15.1% of older Americans (ages 62 to 85) were at risk for a severe drug interaction in 2011, including prescription drugs that may cause:

- Overdose or withdrawal by blocking or stimulating the release of opioids into your bloodstream, including antibiotics, antifungals, drugs for rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, and HIV.

- Symptoms of serotonin syndrome — such as rapid heartbeat, high blood pressure, poor muscle coordination, fever, confusion, and seizures — including amphetamines, antidepressants, anti-migraine medications, anti-nausea medications, antibiotics, anti-retroviral medication for HIV and Lithium.

- Other substances or drugs with similar interactions include alcohol, over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold medicines, marijuana, and illegal drugs (LSD, MDMA or ecstasy, and cocaine).

- Irregular, slow, or rapid breathing or heart rate, including anti-anxiety drugs, antihistamines, anti-nausea drugs, antipsychotic drugs, anti-seizure drugs, drugs to treat Parkinson’s disease and sedatives

What Other Substances Do the Elderly Misuse?

While misuse of prescription or OTC drugs is often accidental or inadvertent, some deliberate abuse also occurs.

- Alcohol is the most abused substance, with binge-drinking — usually defined as five or more drinks at a sitting for men, four for women — on the increase among the elderly.

- The rate of heroin use among the elderly has been on the rise, more than doubling from 2012 to 2015.

- Fentanyl is an occasionally prescribed opioid, but its illicit production, substitution, and adulteration have led to many overdose deaths, including older musicians Prince (age 57) and Tom Petty (66).

Why Do the Elderly Misuse Prescription Drugs?

Older adults face a lower risk of addiction — the worst level of SUD — than younger people. Addiction is most likely when substance use starts before the mid-20s, while the brain is still developing.

So, older brains are less prone to use more and more of a drug because they develop tolerance or to avoid withdrawal symptoms. That does not make them immune, however.

In 2018, nearly 1 million adults aged 65 and older had a substance use disorder (SUD). From 2000 to 2012, the percentage of adults 65 and older among SUD treatment admissions more than doubled from 3.4% to 7.0%. Between 2013 and 2015, it rose another 50% or more.

Risk factors for older adult onset drug misuse include pain control and co-occurring disorders or dual diagnosis.

Pain Control

Pain is one problem that increases as we age. Our bodies wear out, we injure ourselves, or we develop fibromyalgia, neuropathy, or post-surgical pain. Opioids control pain.

As the addictive nature of these new opioids became apparent, physicians and governments began limiting their use. To prevent abuse, some physicians resorted to off-label prescribing of skeletal muscle relaxants as an alternative for pain control.

(In 2016, however, more than two-thirds of individuals with a prescription for skeletal muscle relaxants also used opioids.)

The restrictions on opioid prescriptions had the unintended consequence of sending senior citizens and others with first-time addictions to seek out illegal and less safe alternatives.

Some turned to heroin, but what most wanted was oxycodone and hydrocodone from whatever source could supply it, even black market drug dealers.

Instead, the dealers (who could not get oxycodone, either) often substituted — without telling their clientele — the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which is up to 100 times as potent as morphine. Sometimes they pressed it into pill form and said it was oxycodone or mixed it with other opioids or non-opioids, such as cocaine.

Because the potency was so much higher for fentanyl, only a little was necessary, but even a tiny error could make the fake drugs lethal.

From 2004 to 2008, emergency department visits by older adults for opioid overdoses increased 121%, and fentanyl was one reason for the increase.

Co-occurring Disorders (Dual Diagnosis)

The older adult population has higher rates of multiple chronic illnesses at the same time — including mental health issues and substance use disorders — than the general population: co-occurring disorders or comorbidities.

When the issues are mental health and substance use disorder, it is also known as dual diagnosis. In such cases, substance use may start as an attempt to treat the symptoms of mental health problems. The mental illness may also begin as a result of substance use.

Not many physicians know how to recognize dual diagnosis in general. Among the elderly, it can be even more difficult because symptoms, such as mental confusion and loss of memory, are similar to those of normal aging.\

Other Risk Factors

Other factors that place older adults at risk for SUD include:

- Gender. Older women, for whatever reason — depression and anxiety associated with lower income, outliving a spouse — are more likely to use and so misuse addictive prescription medicines such as benzodiazepines and other psychotropic drugs.

- Social isolation. Lack of a social safety net increases the odds of SUD.

- Past substance use disorder. Addiction has no permanent cure. Relapse is always possible.

Identifying SUDs among the Elderly

Substance use disorder in older adults remains a hidden problem because not all or even many primary care physicians (PCPs) ask about it. PCPs routinely ask about smoking and alcohol but don’t ask about the misuse of prescription drugs or illicit substances without cause because:

- They believe older patients are less likely to abuse them.

- They have limited time with clients; asking about SUDs would take time away from other services.

If physicians impress on their older clients that not knowing what substances they are using could have harmful consequences, they may be more willing to share. One geriatric psychiatrist who did was surprised that her clients, including those in their 80s, admitted to using alcohol and drugs.

While asking every client won’t necessarily uncover the true scope of the problem, it is more likely than maintaining silence.

Signs of Prescription Drug Addiction

It may also help if you can recognize signs of substance misuse. These include if an older adult:

- Obtains identical prescriptions from different doctors or gets them filled at more than one pharmacy.

- Often talks about their prescriptions, sometimes defensively.

- Worries about not having enough of a prescription or leaving the house without it.

- Takes it more often or in larger doses than prescribed on the label.

- Appears angry, confused, forgetful, or withdrawn.

- Becomes increasingly isolated from family and friends.

If you notice these behaviors, bring them up with the older adult’s primary care physician or family and friends. Together, you may convince the senior to find help. According to some sources, older adults are more willing than younger people to go into treatment when asked and more likely to finish the course of treatment.

Treatments for Elderly with SUDs

The 2018 National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) publication Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition) says while there are no treatment plans specifically designed to address addiction in the elderly — although there are a couple of promising alcohol use disorder programs — as there are for adolescents, the existing plans can work as well on them as on younger people.

These plans include behavioral therapies and pharmacotherapies.

Behavioral Therapies

Addiction is an illness, but unlike germ-based diseases that respond to antibiotics, addiction treatment depends on the client wanting to get well and working toward it. These are primarily talk therapies, such as psychological and psychiatric counseling or psychotherapy, and are the most evidence-based treatments for SUD.

They include:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy: Replacing maladaptive behaviors with healthier ones

- Contingency management: Reinforcing abstinence and positive behaviors with tangible rewards.

- Motivational enhancement therapy: Counseling to help the client develop self-motivation and plan for a sober life.

- The Matrix Model: Counselors develop a non-confrontational, non-parental relationship that protects the client’s self-esteem and leads to long-term sobriety.

- 12-step facilitation: Encouraging clients to join Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, or other peer fellowships to maintain sobriety.

Pharmacotherapies

Almost all SUD treatments begin with detox: stopping drug or alcohol use until the substances leave your system and you complete the withdrawal.

Some SUDs are too difficult for some people to quit on their own. It’s not a matter of will-power or character. Addiction changes the brain, affects its chemistry. You can become programmed to drink or use opioids. Other addictions — particularly to alcohol and benzodiazepines — may be too deadly to stop cold turkey.

Sometimes you need a little more help than behavioral therapy alone. With alcohol, the amount can be tapered off slowly, minimizing withdrawal pain, but, for opioids, a more common method is medication-assisted treatment (MAT): substitution of a weaker, safer opioid that controls the debilitating withdrawal symptoms without producing a euphoric high.

Some critics, even within the medical profession, dismiss this as exchanging one addiction for another. Without behavioral therapy, they could be right. The difference is that MAT allows clients to function — to continue working, taking care of themselves, and contributing to society — while getting treatment, instead of obsessing about obtaining and using drugs.

Examples of MATs include:

- Methadone. Mainly a heroin substitute. Concerns about its misuse mean it is only administered daily in a physician’s office or clinic. It is also used for the treatment of chronic pain because it is long-lasting.

- Buprenorphine. Mainly an opioid substitute. It is prescribed as a sublingual (under the tongue) dissolving tablet or film, a 6-month implant, and a once-monthly injection. It controls the craving that leads to withdrawal.

- Naltrexone. An anti-opioid. In its injectable, once-monthly formulation, Vivitrol, it prevents opioids from taking effect, eliminating the reason to use them. Its major drawback is that the client must complete withdrawal before it can be started.

- Naloxone. An opioid antidote. It is mostly used to reverse an opioid overdose because it cancels the opioid effects. Also used or in combination with buprenorphine as Suboxone to discourage misuse.

How to Avoid Misuse

To avoid accidental misuse, older adults should:

- Follow the medication’s directions. A pill caddy with each day’s doses (sometimes parceled into individual times) can make this easier.

- Tell your physician every OTC pill, drug, and supplement you take, how much alcohol you drink, and if there are any foods you should avoid. Even spices can have drug interactions.

- Ask about side effects and interactions.

- Never share your meds with someone else or use theirs.

- If a medication doesn’t work, tell your physician. Don’t increase a dose on your own.

Studies on the elderly and substance use, misuse, and abuse are still in their infancy. Until the U.S. surgeon general’s 2016 report Facing Addiction in America, the government seemed more interested in punishing drug use rather than treating or preventing it. Addiction research is still playing catch-up.

Fortunately, the same programs that help younger people also appear to work for the elderly. It’s just a matter of getting them together.

Sources

Medical disclaimer:

Sunshine Behavioral Health strives to help people who are facing substance abuse, addiction, mental health disorders, or a combination of these conditions. It does this by providing compassionate care and evidence-based content that addresses health, treatment, and recovery.

Licensed medical professionals review material we publish on our site. The material is not a substitute for qualified medical diagnoses, treatment, or advice. It should not be used to replace the suggestions of your personal physician or other health care professionals.